Amedeo Bertolo was born in Milan on September 17, 1941, to a Friulian family. By some curious fate, he grew up in the same public housing buildings where Giuseppe Pinelli and Pietro Valpreda also lived, though he would only meet them years later, and in other contexts. From his father, a mosaicist with whom he worked for a year, Amedeo learned to create designs that, tile after tile, required time, patience and determination to realize.

After his classical studies, he was accepted to the Department of Agriculture at the University of Milan (“it was the shortest registration line,” he admitted), and would remain there even after his graduation as a professor of agricultural economics (perhaps this explains his recurring agronomic metaphors such as the one on anarchism and alcohol content).

But well before starting to teach, his public life began with a booming event: the first political kidnapping of the post-war period, that of Isu Elías, the Spanish Vice Consul to Milan. The act was carried out together with a group of young Italian anti-fascists in order to save the life of Jorge Conill Valls, a Spanish anarchist condemned to death by Franco’s regime (a verdict that would later be changed to life in prison).

From there began a militant activity that would accompany his entire existential journey, solidifying towards the end of the Sixties with the formation of the Gruppi Anarchici Federati (GAF). While only one of three national anarchist federations active at the time, the GAF were unique for their youthful composition and their affinity-based organization within the federation. It was a powerful experience for Amedeo that came to an end with the GAF’s self-dissolution in January 1978, an event foreshadowing the transition away from the idea of a movement-party to the idea of movement-community. It was out of this shift that an expansive “brotherhood” would be born, one destined to endure.

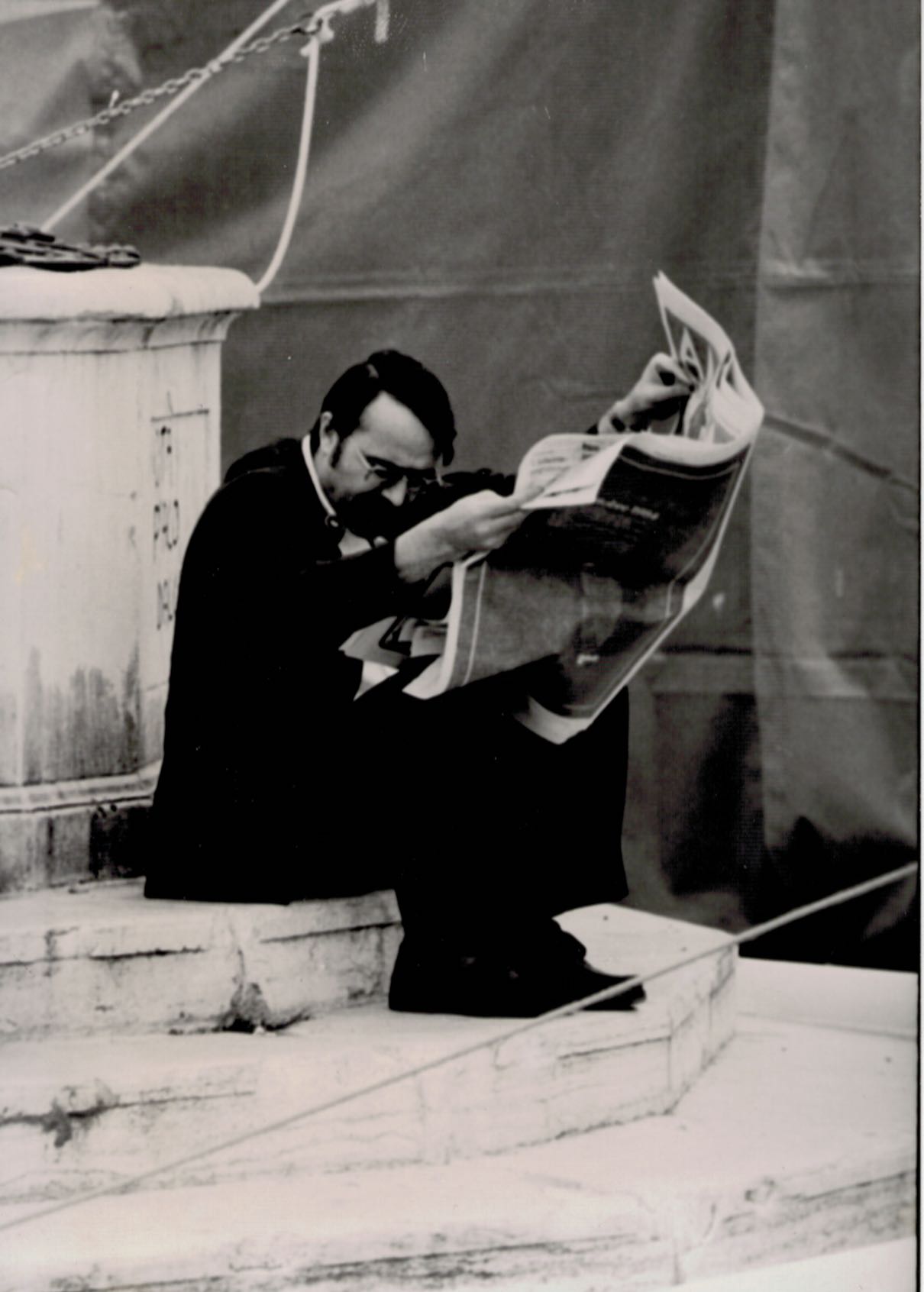

Those years made him protagonist of another crucial historical moment, one coinciding with the Italian State’s “strategy of tension” and the resultant counter-information activities adopted by the Crocenera (Anarchist Black Cross), which he and Giuseppe Pinelli had founded in 1968. The two men had met through Bandiera Nera (Black Flag), an anarchic group based in Milan, and the anarchic club Ponte della Ghisolfa, also in Milan. A year later came the Piazza Fontana bombing, falsely attributed to anarchists by important State officials, and then Pinelli’s violent death, tossed from a window at Milan’s police headquarters. These events marked the height of anti-anarchist propaganda, dismantled in the months that followed by a formidable counter-information campaign (the Crocenera, for example, published a book entitled, The Boss’ Bombs: People’s Trial of the Italian State and the Milan Bombing Investigators). At first a solitary campaign – Hysterical Press Conference at Circolo Ponte della Ghisolfa ran one major headline – it soon became widespread.

Yet the Sixties were not just assassinations, subterfuge, sham trials and “State slaughters.” They were also the years of the revamped libertarian creativity that led to 1968. It is no coincidence that midway through the decade, young European anarchists invented a symbol to match the new anarchic imagination: the circle-A. Thanks to its simple iconography, the symbol would quickly conquer walls all over the world. While conceptualized in Paris (Tomás Ibáñez used the symbol for the first time in the newsletter “Jeunes Libertaires”), its “graphic debut” was made in Milan, where Amedeo Bertolo, with the help of an upside-down glass, carved it on the stencil for the first mimeographs made by the anarchist group Gioventù Libertaria. This same group opened the first club named after Wilhelm Reich, an obvious nod to the sexual revolution. They also organized the international libertarian “Provotariat” in Milan, deciding to experiment with a kind of “ambrosian rite” similar to the cultural provocations being performed by the Provos movement in the Netherlands.

Added to this militant activity was an editorial one: ancillary at first, it slowly became the priority. While he only released three slim editions of “Materialismo e libertà” (“Materialism and Freedom”) in the Sixties, Bertolo, together with others, founded the monthly “A rivista anarchica” (“A/Anarchic Magazine”) in 1971. The money that gave life to what was (and still is) the best-selling anarchic newspaper in Italy were actually investments intended for another project: an anarchic commune in the Siena countryside. But the idea had trouble taking off amidst the tumultuous events of 1968-1969, and the financiers decided to divert their funds to a magazine “of struggle and reflection” more in line with the times. Remaking himself journalist and graphic designer, Amedeo worked on the monthly until 1974, when he handed it over to the other writers and began collaborating with two other publications: the international quarterly “Interrogations” (in print from 1974 to 1979) and “Volontà,” (“Will”) a journal of theoretical analysis (which he edited from 1980 until its closure in 1996).

With the Centro studi libertari “Giuseppe Pinelli” (“Giuseppe Pinelli” Center for Libertarian Studies), founded in 1976 in Milan and still active, he organized and participated in dozens of conferences, seminars, round tables, conventions and debates, mostly in Italy but also abroad, in a continuous effort to keep up on the libertarian thought and experimentation emerging in different fields across the world. While this undertaking may have had its peak in 1984 with the international anarchist meeting “Venice ‘84,” attended by thousands of people from over thirty countries, Bertolo would continue organizing anarchist-related events for many years to come.

And his editorial and cultural activity did not stop there. Over the years, in fact, his attention moved from periodicals to books. He first joined the publishing house Edizioni Antistato, active from 1975 to 1985; then, in 1986, he founded elèuthera, giving life to yet another collective adventure that has lasted over thirty years.

He died in Milan on November 22, 2016.