Anarchist Saints and Martyrs: Portraiture in the "Cronaca Sovversiva" (1903-1920)

di Andrew Hoyt

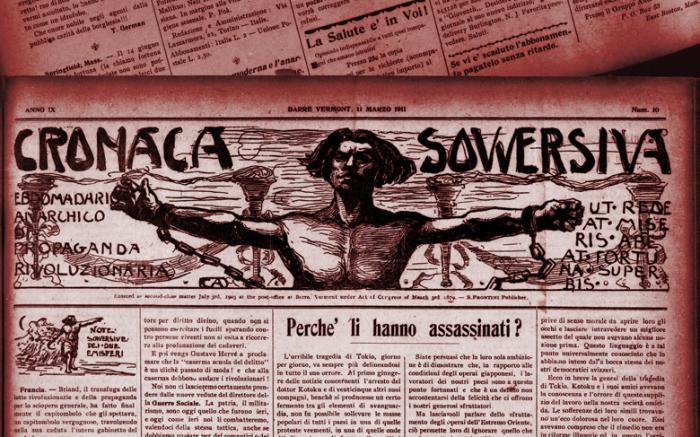

In this paper, I look at the Italian language anarchist periodical the Cronaca Sovversiva (1903-1920) which circulated throughout the Atlantic world and played a vital role in the construction of a transnational social movement across the widespread Italian emigrant labor diaspora. An examination of this newspaper reveals the propaganda tactics of the newspaper’s principle creator, Luigi Galleani, and the artistic choices of the newspaper’s primary printmaker, Carlo Abate. I argue that Abate’s prints, in particular his portraiture, were used to create a transnational revolutionary hagiography on the pages of the Cronaca Sovversiva. Abate’s work thus provides a noteworthy example of how the transnational circulation of anarchist print culture contributed simultaneously to the formation of a diasporic revolutionary identity and to transnational debates about the role of the artist in an age of mechanical reproduction.

The Cronaca Sovversiva’s contents inform not only the communities behind its publication, but the audience of migrant workers to whom it was addressed. The utilitarian purposes, ideological content, political tactical deployment, and visual iconography of this print culture need to be incorporated into our understanding of the Italian immigrant experience. Galleani helped form this counter-public imaginary by consistently bringing his readers’ attention to individuals who had made great contributions to the cause of anarchism with their minds, their actions, or their lives. One of the most effective ways for Galleani to create a transnational culture of insurrection was through the use of images, and it was these images which Abate was asked to create.

The publication and consumption of this propaganda enabled marginalized migrants to access a radical transnational identity which helped them interpret their lives and their labor while also encouraging pragmatic and real world ways to enjoy life, despite the tumult of immigration and dislocation. Radical newspapers were the major connection between the widespread nodes of the anarchist network, serving multiple functions within their communities: facilitating the exchange of resources, the movement of people, the creation of identity, the exchange of money, the spread of tactics, and the mobilization of collective action around different issues.

An examination of the paper highlights issues that contributors found important and reveals tactical choices geared towards imaging both historic and current events in a way to build transnational identity. The Cronaca typically contained four oversized pages; the first page usually addressed either commemorations or current events. The last page was filled with financial information and notes from anarchist groups spread throughout the United States. The middle two pages contain a mix of Galleani’s articles and other sections including serialized stories of anarchists and the occasional poem.

Besides creating several different mastheads for the Cronaca, Abate provided images to accompany articles. This was particularly common when the articles related to historic events. In fact, the prominence of images of the Haymarket Martyrs and the Paris Commune demonstrates how Galleani used Abate’s contributions to the paper. For example, the 1907 masthead consists of a woodblock image depicting five portraits of the Haymarket Martyrs. The visual representation of these historic people and events provided readers with prominent reference points for forming an anarchist historic consciousness in much the same way national histories help shape national imagined communities. Examining this material can therefore help us understand how the transnational circulation of radical tradition shaped immigrant identities.

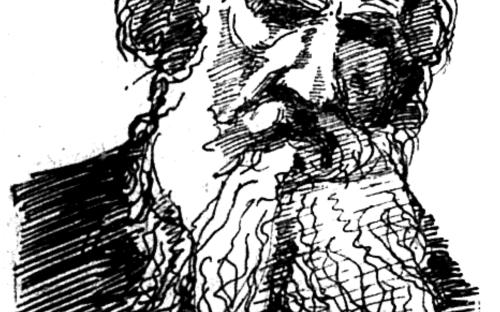

Abate’s art shows an awareness of the way anarchists were persecuted and contributes to the circulation of images that form the backbone of the anarchist imaginary. Abate does this by not only portraying historic events but also current ones. For example he provided images of those executed by the Spanish state following the Tragic Week of 1909, such as Jose Miguel Baro, Eugenio Del Hovo and Garcia Clement as well as the man who attempted to assassinate Alfonso XIII in 1906, Mateo Morral. This is another example of the use of Abate’s art to form a visual martyrology and hagiography of militant anarchists. These men, less well known than the famous propagandists Bakunin or Kropotkin, demonstrate the kind of self-sacrifice and vengeance idealized by Galleani, and Abate’s rendering transformed their names into faces for the readers.

In his portraits, Abate finds different ways to demonstrate his hand, always preferring to express human emotion and human labor rather than photographic similitude or strict visual veracity. Images like Reinsdorf demonstrate Abate’s vocabulary, employing engraver-like shading details on the coat and in the hair as well as stippled round cutouts. All of these portraits show how Abate was composing his prints to express a romantic rendering of his subject to provoke an emotional response in his viewers. These images are accessible and they could be cut out of the paper and saved as mementos or anarchist icons; they function not unlike Catholic saints, showing that real people can commit what Galleani saw as selfless acts of “propaganda of the deed” and be remembered by the community.

These images display Abate’s ability to approach portraiture, even on the mass-production scale needed for Galleani’s paper, with a range of techniques and vocabularies which all maintain a kind of consistency not difficult to group together and identity — each appearing easily and naturally drawn by nothing other than a human hand. Scenes surrounding major historical events such as the Paris Commune or the trial preceding the execution of Francisco Ferrer in Spain show how Abate recognized he had to compete with photomechanical processes, since woodblock engravings and halftones provided the same service to mass media print culture. However, Abate remained consistent in his aesthetic stand and his visual representation of action scenes and narrative moments continued to display his long-standing artistic and political values.

By using Abate’s art, Galleani raises the significance of the event in the corresponding article to another level, helping the readers identify with the victims and distinguishing the most significant events from the more everyday reports of strikes and repressions, which commonly fill the newspaper’s pages. The sketchy feel to Abate’s images must be understood as intentional. After all, the black lines are the ones he has not cut away and are thus easy to correct and eliminate. It is this choice to leave this roughness around the edges, the intentional lack of clarity or seemingly sloppy errors which Abate uses to assert his humanity, the very fallibility which photography is so proud of eliminating in images such as portraiture. In this way he conveys his solidarity with artisans and craftsmen, with working artists over machines and virtuosic and slave like performances of mimicry that were increasingly becoming a part of the American school of wood engraving.

Carlo Abate and Luigi Galleani generated a radical transnational identity while existing in a world of highly mobile and destabilized communities. They did this through the production and circulation of print culture that drew attention to certain historic narratives, valorized certain modes of resistance, created an alternative martyrology and hagiography, and encouraged a revolutionary calendar of commemoration. Examining this material allows us a peak into their imaginative realties, a look at the stories, heroes and nemesis which shaped their historic consciousness and provided them with a cultural lexicon of revolution.

During Abate’s long collaboration with Galleani the two men helped create one of the most visually vibrant and politically radical newspapers of the Italian Left. The print culture they left behind is like a palimpsest with layer after layer of meaning hidden in its conception, manufacture, presentation, and consumption. Building a contextual and temporal sense of the print culture of the Galleanisti allows for a more nuanced reading of both Galleani’s propaganda tactics and Abate’s syntactical visual rhetoric, showing how they coincide and reinforce a similar set of radical values and instincts.

Abate, like Galleani, remained consistent with his roots in the radical transatlantic world of the long nineteenth century. His art, like Galleani’s editorial composition of the paper, reveal their particular personalities and ideologies. Like the immigrant populations and working class migrants amongst whom they lived and for whom they wrote and published, Galleani and Abate represent a marginalized and largely obscured chapter in history. However, the print culture they produced not only supported their movement and community but manages to linger on, whispering to us a century latter. It is in the implications and meanings of their lives’ work that we are able to find hints of who they were and how they interacted with the world.